OTTOMAN RULE

1430-1912

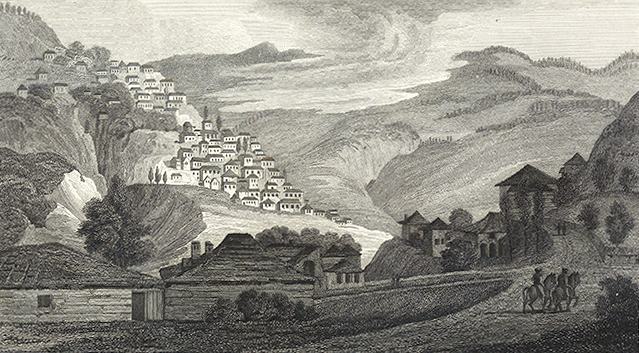

It is estimated that the Ottomans conquered the area of Epirus and Metsovo in the mid-15th century. Metsovo was incorporated in the Trikala sanjak (administrative district) and, from the mid-19th century, in the Ioannina pashalik. The situation would not change until 1912, when the First Balkan War marked the end of the Ottoman rule. During these five centuries, the Vlach speaking population of the mountainous area of Metsovo participated in the economic life of the vast empire by paying the taxes imposed by the central administration and by developing trade relations with a wide network of centres, including Istanbul but certainly not limited to Ottoman borders. At the same time, Metsovo formed an integral part of the Ottoman administrative and military organisation, at times serving as the headquarters of Ottoman officials. The changes taking place in the empire, especially the Ottoman reforms of the 19th century, could not but affect the evolution of the Metsovo population and economy. From the mid-19th century, Metsovo saw strong economic growth, the development of education and the construction of utility infrastructure thanks to the legacies of a number of benefactors.On October 9, 1430, Ioannina surrendered to Sinan Pasha, beylerbey (administrator) of Rumeli. It was the beginning of Ottoman rule across large part of Epirus.

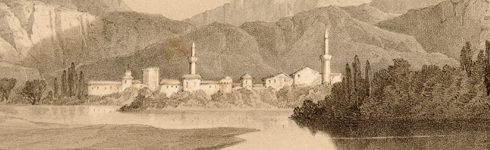

Ioannina, in a picture taken in the mid-19th century by Frédéric Boissonnas.(Thessaloniki Museum of Photography)

The term “Rumeli” was used to describe a large administrative district that included the territory of the Balkan peninsula. In other words, it represented the Ottoman possessions in the Balkans. ‘Rumeli’ means “land of the Romans”, i.e. land of the Byzantine Empire which called itself “Roman Empire”. During Ottoman rule, Christian residents of the Balkans were called “Rum”, from which the name “Romioi” originates.

According to the census carried out by the Ottomans in 1454-55, Metsovo, along with six other settlements (probably: Milia, Anilio, Voutonosi, Derventista/Anthohori, Koutsoufliani/Platanistos and Malakasi) formed a kind of “community”, known as “Horion Metsovou”. It belonged to Omer bey as part of the fiefdom, in the sanjak (administrative district) and kaza (province) of Trikala. 700 families were subject to taxation; 41 widows and 52 single men and women were recorded in total.

According to the census carried out by the Ottomans in 1454-55, Metsovo is inhabited by 700 families subject to taxation, 41 widows and 52 single men and women.

Metsovo, in a picture taken in the end of the 19th century by Frédéric Boissonnas. (Thessaloniki Museum of Photography)

The administrative structure of the Ottoman state was based on specific political and financial mechanisms. The names of the administrative divisions, as well as their geographical designation, changed over the centuries. The sanjak was a subdivision of “eyalet”, which was a large district such as Rumeli. The sanjak administrator was called “sanjak-bey”.

In 1659, Sultan Mehmed IV granted tax and political privileges to the residents of Metsovo due to the services they offered as “derbentzides” (guards of “derveni”/mountain pass). The residents of the area of Metsovo were exempt from the ordinary and extraordinary taxes levied on Christian subjects in other areas, provided that every year they paid the corresponding tax in advance and in a lump-sum

Oral lore has it that Kyriakos or Kyrgos Flokas, a leading shepherd from Metsovo, contributed greatly to the granting of the privileged status to the area by the Ottomans. He was favoured by a Grand Vizier* who rewarded Kyriakos for sheltering and protecting him when his life was in danger from the Sultan

*The Grand Vizier was a form of “prime minister” in the Ottoman empire. The post holder acted as head of the Imperial council (Divani), the second highest in rank in the empire after the Sultan.

In 1659, the Exarchate of Metsovo was founded and was supervised by the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The Exarchates were ecclesiastical districts subject directly to the Ecumenical Patriarch and not to the Metropolises’ system. The Patriarch would pass the management of the exarchates to citizens, along with the right to collect the ecclesiastical contributions and the duty to provide Christians with spiritual leadership. The division into patriarchal exarchates started in the 14th century during the Byzantine rule, further developed during the Ottoman rule and abolished in the 19th century.

There are no patriarchal documents to confirm the year when the Exarchate of Metsovo was founded. The first relevant text that mentions the Exarchate of Metsovo dates back to 1808. It is therefore possible that the Exarchate may have been founded before 1659.

A voivode (high-rank Ottoman officer) was nominated to head the administration of Metsovo in the 17th century.

In the 17th century, the division of mukataa was introduced to the Ottoman empire: any person who did not belong to the hierarchy of the fiefs was permitted to collect an area’s taxes after having deposited a pre-defined amount of money with the state treasury. The person who collected these taxes was also the administrator of the area.

If the area was a kaza, its administrator was called a voivode. A voivode administered Metsovo from the 17th century onwards.

In 1719, the French built a storehouse in Metsovo and filled it with products made by the Vlach population that they planned to export.

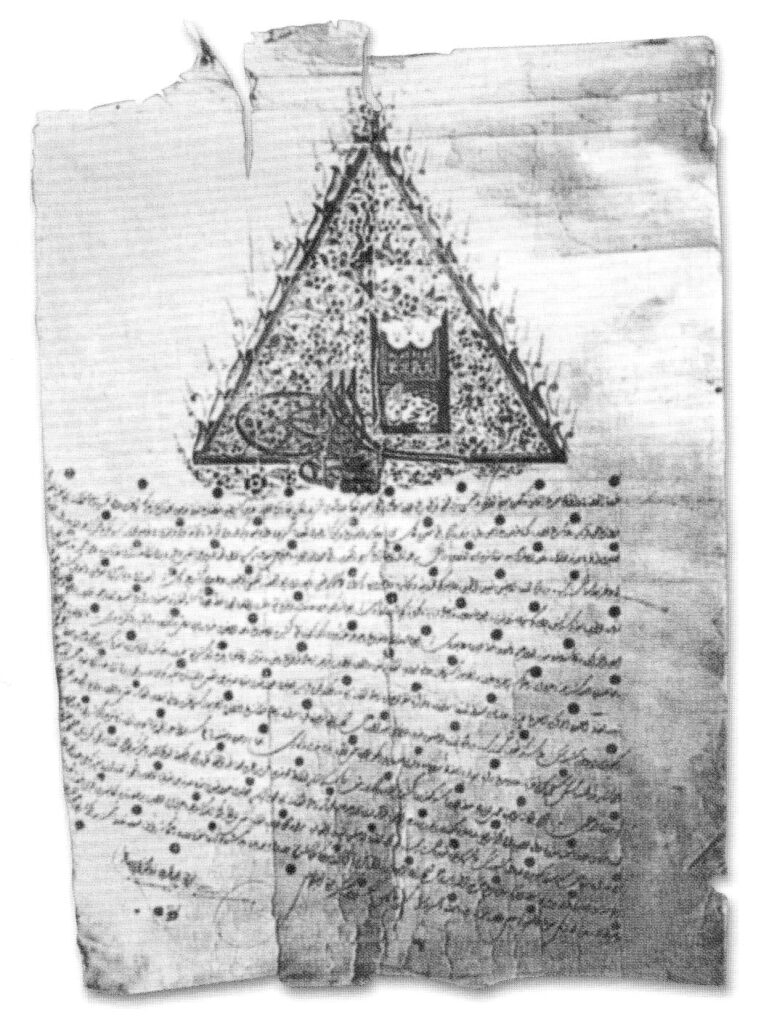

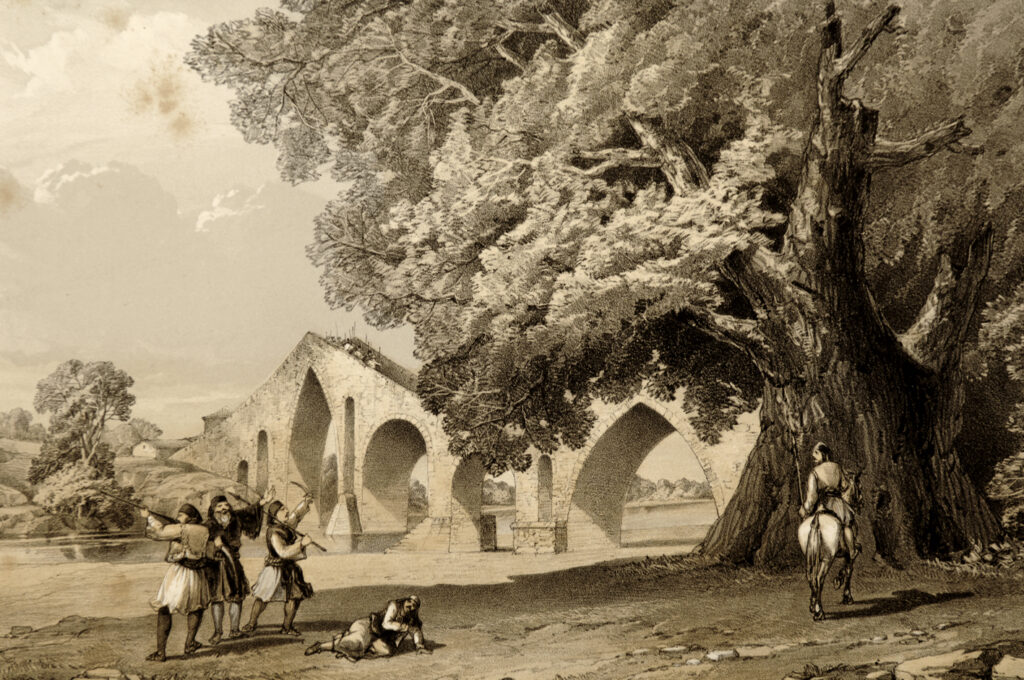

The Zygos pass, on the most important transportation networks connecting Epirus and Thessaly.(Colour lithography – Louis Dupré, 1825)

The French explorer Pouqueville reported that since the era of Louis XIV (17th century) the Vlachs had supplied wool and leather to the French. From the 18th century onwards, there was a rise in exports and traders from Metsovo established trading houses in Venice, Naples, Trieste, Marseilles, Vienna, Moscow, Odessa, Constantinople, Thessaloniki, Serres and Alexandria. Metsovo became a centre of trade even more important than Ioannina.

On May 25, 1759, the Greek school of Metsovo was officially founded thanks to a donation from Sterios Stanos.

The term “Greek school” normally refers to secondary education establishments but in most cases, the Greek school also included a primary school. Metsovo had schools before this date, at least from the start of the 19th century, but 1759 was when the Greek school was officially founded. This corresponds with the Ottoman authorities’ authorisation of the restoration of the church of Aghia Paraskevi— its cells would serve as the school’s classrooms until 1817. This first school had one teacher and two tutors whose expenses were covered by donation by Stanos, revenues from the Monastery of Aghios Nikolaos and other bequests from Metsovo residents.

According to a 1766 letter regarding the hiring of teacher Triantafyllos Kyrkos Stanos: “…the undersigned priests and administrators of the area of Metsovo agreed that Mr Triantafyllos Kyrkos Stanos would provide Greek lessons for seven full years.»

In 1787, Ali Pasha became the administrator (Derbendler) of the Trikala sanjak area to which Metsovo belonged. He then became the Pasha of Ioannina.

Ali Pasha Tepelena (1741-1822) created a “state within a state” and ruled over the largest part of the western Ottoman provinces, taking advantage of the weakness of the Sublime Porte. At the peak of his power, he governed a large area including a large chunk of modern Albania and modern Greece. A charismatic leader, he amassed incredible wealth and successfully created a powerful army and an effective administrative mechanism. Tolerant towards the other religions, he appointed many Christians to higher military and administrative positions.

In 1818, the Exarchate of Metsovo was passed to the School of Greek Language (Greek school) of Metsovo.

From this point on, the Exarch was no longer a natural person (an individual) but a legal entity (the School). The School supervisors elected a person to perform the duties of the Exarch and undertake the administration on their behalf. As a result, the Exarchate was now under the control of the residents of Metsovo.

In 1831, Metsovo becomes a nahiye (municipality) and is officially incorporated into the Ioannina pashalik. For the first time a Turkish administrator (muhafiz) is put in charge.

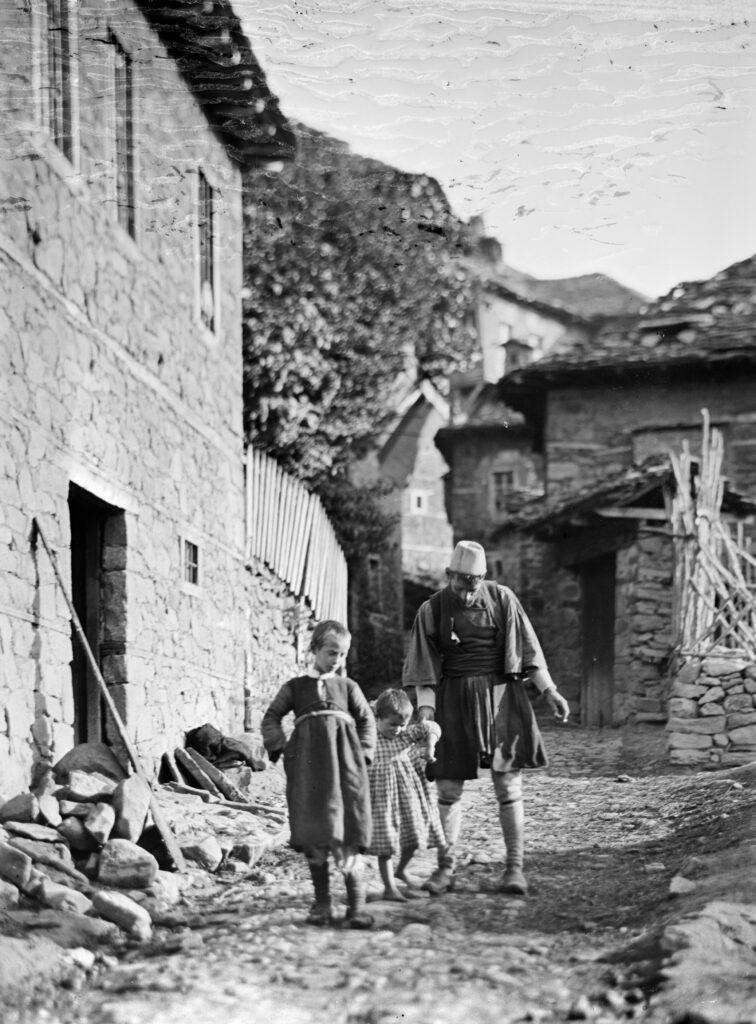

Alley in Metsovo, in a picture taken in the end of the 19th century by Frédéric Boissonnas. (Thessaloniki Museum of Photography)

This administrative change demonstrates that Metsovo was an important settlement, in terms of its population.

A fire destroyed the Greek School that had been built thanks to a donation from Dem. Zamanis. The library, containing 4000 books and manuscripts, was razed. After the incident, the school operated in the cells of the church of Aghia Paraskevi.

In the 19th century, Metsovo had five schools: one nursery school, one girls’ school, two primary schools (the central one and that of Aghios Demetrios) and one secondary school consisting of two classrooms.

A müdir (nahiye administrator) was established in Metsovo in around 1850.

The nahiye was a subdivision of the vilayet or kaza and had a more uniform territory. During the Ottoman reforms, the nahiyes were granted relative administrative independence and their administration was assigned to müdir officers.

Nikolaos Stournaras, one of Greece’s national benefactors, died in Halkida.

Nikolaos Stournaras was born in Metsovo in 1806. He was the nephew of the benefactor Michael Tossizza (whose sister was Stournaras’ mother). Once he had completed his studies in his hometown, he went to Livorno in Italy, where he worked at the trade house of the Tossizza family. He was later sent to Paris to study at the School of Trade and Industry after which he moved to Alexandria where he worked as an assistant to his uncle, Michael Tossizza and then as the director of the trade house of the Tossizza family. He bought large plots of land in Fthiotida and at the same time, donated significant amounts of money to educational institutes and established charities in Alexandria and Athens in addition to helping to fund the construction of a school in Metsovo. In 1853 he went to Greece to work on a number of development projects but died suddenly. In his will, he left significant amounts of money to charitable causes, the schools in Metsovo and Alexandria and for the foundation of a technical school in Greece.

In 1854, during the Crimean War, revolutionary movements emerged in Epirus under the leadership of General Theodoros Grivas. The residents of Metsovo were divided by the revolution, with some supporting it and others not. The latter group asked the Turkish armies from Ioannina to intervene and in March 1854, after three days of fighting, the Turks pushed Grivas from the city. Metsovo was looted and 400 houses were set ablaze. This ransacking is now referred to as “the Destruction of Grivas”.

Theodoros or Theodorakis Grivas (1797-1862) was a Greek Revolution fighter coming from Preveza. He participated actively in the political life of the independent Greek state but without coming out in support of any specific party or principles. In 1836 he supported Otto, the then king of Greece, and put down the revolt against him in Acarnania, however in 1862 he launched a revolution against Otto and succeeded in occupying Vonista and Messolonghi. When the Crimean war broke out* he crossed the Greek-Turkish borders with a group of irregular troops to lead a revolt in Epirus. The confrontation between Grivas and Otto is reflected in the popular song «My dear Grivas, the king wants you».

*The Crimean war (1853-1856) was a conflict that took place between Russia, on one side and the UK and France on the other. The war is also known as the ‘Eastern War’. When Russia attacked the Ottoman empire, the UK and France rushed to support the Sultan. The war ended with Russia’s defeat, but Europe also suffered the consequences of the war, namely the destruction of the “Holy Alliance” and a shift in the international status quo that proved to be painful for Greece as well. During the war, revolutionary movements for the liberation of Epirus, Thessaly and Macedonia broke out but were unsuccessful. In order to punish Greece and force it to stay neutral, the Anglo-French navy occupied Piraeus and baricaded it for the three years between 1854 and 1857.

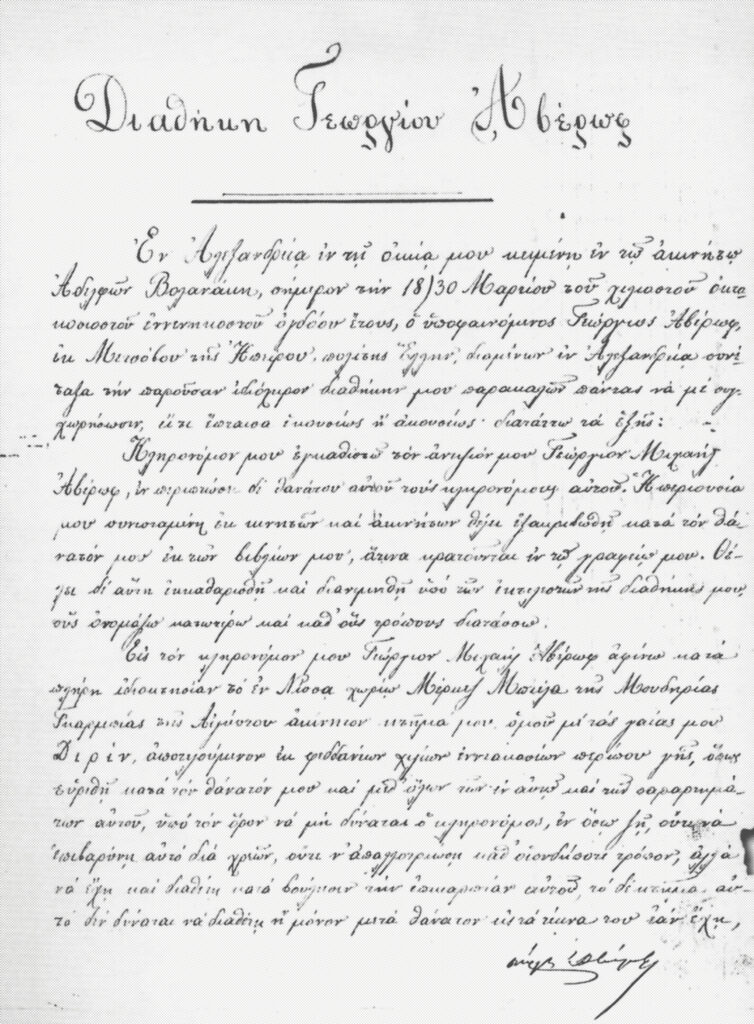

Michael Tossizza, one of Greece’s national benefactors, died in Athens.

Michael Tossizza was born in Metsovo in 1787. In 1806, along with with his brothers, he took charge of his father’s fur processing firm in Thessaloniki. In 1820 he relocated to Egypt where he made a substantial fortune, thanks, among other factors, to the fact that he befriended the regent of Egypt, Mehmed Ali. Michael Tossizza was Greece’s first General Consul in Alexandria and he also contributed to the foundation of the Greek Community. In 1854 he moved permanently to Athens, where he died in 1856. In his will, he left significant amounts of money to help the poor and support health care and ecclesiastical and educational institutions, such as the University of Athens, the Arsakeio School and the Technical School.

In 1864-67 the fort of Metsovo was built, incorporating a mosque.

A picture of the fort taken by Hubert Pernot, a French linguist and Hellenist who visited Epirus in 1913, one year after the liberation of Metsovo. (Hubert Pernot, Neohellenic Institute, Sorbonne)

In 1912, after Metsovo was liberated, the fort gradually collapsed and was covered in earth, thus creating the hill that is still known as the “Castle”.

In 1867, the area of Metsovo temporarily became a kaza.

The kaza was an administrative subdivision of a sanjak and can be understood to be province. Originally it indicated an area under the power of a kadı (Islamic judge). In 1864, however, the law on the vilayets dictated that the kaza was no longer subject to the hierarchy of Islamic judges. The administrative reform of the Ottoman state was completed in 1867 when the Ioannina and Trikala pashaliks become a single vilayet, the vilayet of Ioannina.

In the early 1870s, the “Averoff pharmacy” was founded in Metsovo. It provided the entire city and the residents of the wider area, including soldiers of the Turkish guard, with free medicine.

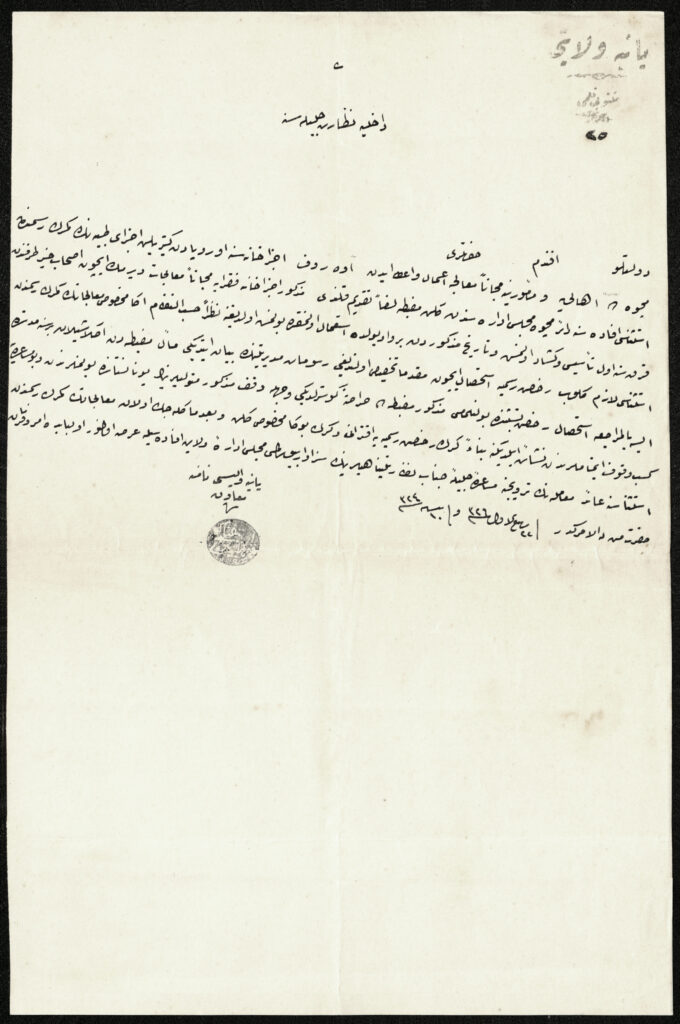

On April 23, 1908, in a letter to the Port (Home Office), a representative of the Vali (governor) of Ioannina requested that the pharmaceutical materials imported from Europe and destined for the “Averoff pharmacy” be exempted from customs charges. The letter says:

“We are sending the attached report of the Metsovo Administrative Council on the Averoff pharmacy, requesting that the pharmaceutical materials it imports from Europe be exempted from duties. The pharmacy manufactures and supplies free medicines to the poor and officials. (…) The Administrative Council of the Vilayet [of Ioannina] therefore requests that the High Home Office, on one hand, grants the pharmacy an official license and, on the other hand, approves the exemption from duties of the necessary pharmaceutical materials and any it will need in the future.” (Başbakanlı Osmanlı Arşivi / Ottoman State Archives, Istanbul).

The pharmacy is believed to have opened its doors in 1816, supplying free medicines to the poor of Metsovo.

In 1875, the area of Metsovo permanently became a kaza; a kaymakam (deputy governor) and a kadı (judge) were also established there. In total, it incorporated approximately 6,000 residents.

The 1864 administrative reforms of the Ottoman state led to a change in the names of the administrative divisions and the related offices.

The empire was divided into vilayets (prefectures or general administrative divisions), which were divided into sanjaks, which themselves were divided into kazas. The kazas, like the kaza of Metsovo, were governed by kaymakams, who were appointed and dismissed directly by Istanbul.

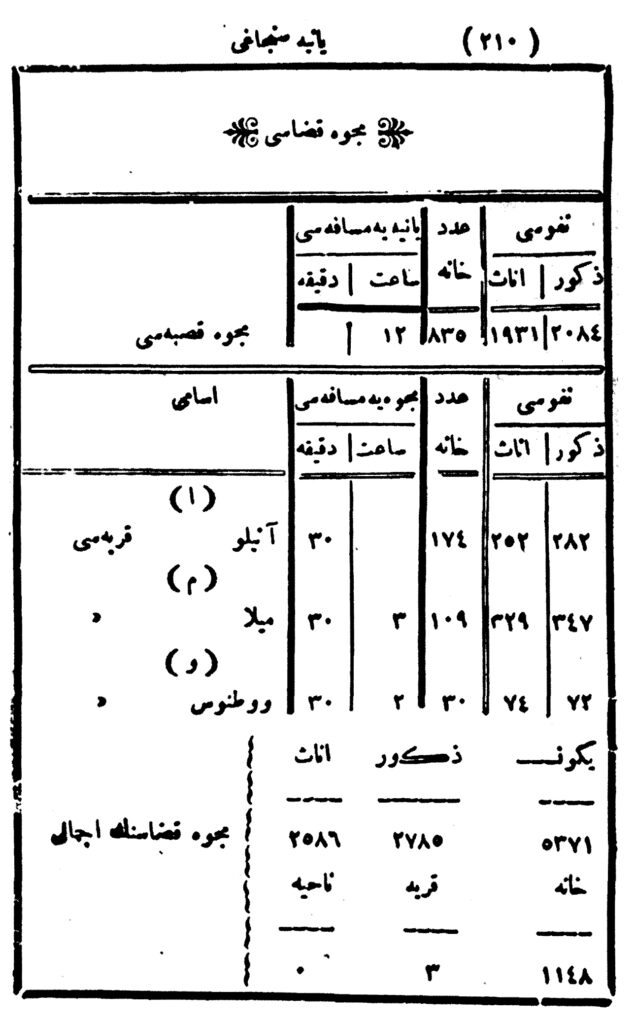

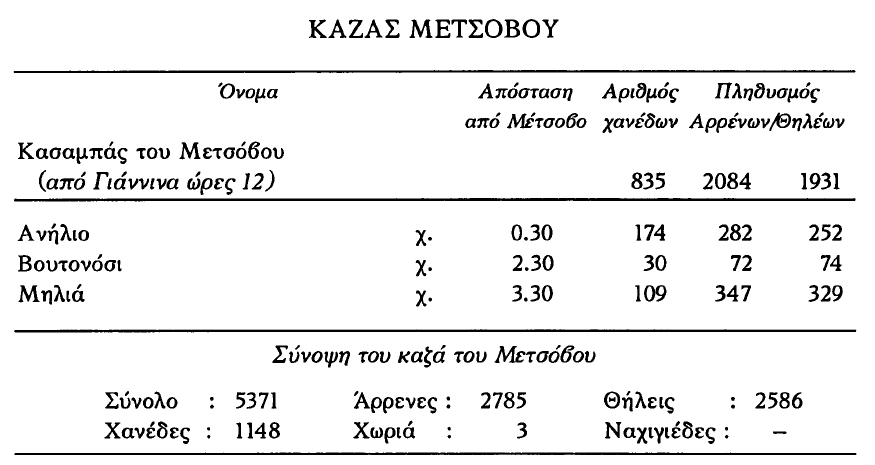

According to the 1895 census – the only published source containing a detailed recording of the population of Epirus during the Ottoman rule – the kaza of Metsovo belonged to the sanjak of Ioannina. In addition to the kasaba (Hora) of Metsovo, it included another three villages, Anilio, Voutonosi and Milia. In total, the kaza of Metsovo had 5371 residents and 1148 hanes (houses).

In 1878, under the pretext of the Russian-Turkish war, a revolt broke out in Epirus that led to a rise in guerilla warfare.

The 1877-1878 Russian-Turkish war represented one of the most serious crises of the Eastern War and ended with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. The victor, Russia, demanded the creation of Greater Bulgaria as part of the Treaty of San Stefano. However, thanks to the intervention of Britain and Austria-Hungary, the treaty was modified at the Congress of Berlin. Romania, Serbia and Montenegro were recognised as independent states. During the war, the Greeks in Epirus, Thessaly, Macedonia and Crete revolted, though unsuccessfully. However, the negotiations at the Congress of Berlin resulted in Greece being granted Thessaly and the area of Arta in 1881.

In 1885, a Romanian school was founded (thanks to a legacy from Demetris Kazakovits from Metsovo), for the teaching of the Romanian language. Its operation was intermittent. It closed in 1901 by decision of the Romanian government but reopened in 1908 (at the house of Kyrgos Topis). The school was destroyed the day after the liberation of Metsovo (November 1, 1912) and its archive was set on fire.

Snapshot of a Vlach wedding at the village of Drossopighi, early 20th century (Foundation of the Museum for the Macedonian Struggle)

The so-called ‘Koutsovlach question’ was an issue related to minorities that emerged in the second half of the 19th century when there was also a rise in nationalism in the Balkans, including Romania. Based mainly on the similarity of the Vlach language to Romanian, Romania claimed the Vlach populations of the Ottoman empire as its own. In the areas of Epirus, Macedonia and Thessaly an intense argument with Greece arose over the identity of the populations, expressed by the foundation of Romanian schools and churches. The antagonism increased at the start of the 20th century (during the Macedonian Struggle); Greek guerilla groups were active in Ottoman Macedonia and Greeks living in Romania were attacked, leading to the collapse of diplomatic relations between Greece and Romania. The Koutsovlach question became less important during the Balkan wars thanks to Venizelos’ approval of the free operation of Romanian schools and churches in areas that were annexed to the Greek state and had Vlach populations. However, the emergence of another factor, namely Italian imperialism, during World War I and into World War II, added a new twist to the problem. In 1917, Alkiviadis Diamantis, a Vlach speaking lawyer from Thessaly, instigated the foundation of a Vlach “Republic of Pindos” but it was not to last. In 1941-1942, Italy, as the occupying power, again with the help of Alkiviadis Diamantis, planned the foundation of an Autonomous Koutsovlach “Principality of Epirus” consisting of Pindos, west Macedonia and Thessaly. The plan was finally abandoned after Italy fell in the summer of 1943.

In January 2, 1890, the Averofeio School of Metsovo opened thanks to a donation from Georgios Averoff. The school was burnt down during the Civil War in October 1947 and the current Primary School was built in its place in 1955 (by the Tossizza Foundation).

The two-storey Averofeio School of Metsovo with its pupils and teachers, in 1890. (Archive of G. Plataris-Tzimas)

Georgios Averoff was born in Metsovo in 1815. At the age of 19, he went to Egypt where he amassed a huge fortune from the trade of dates, fabrics, cotton, etc. Averoff was recognised as a great benefactor because his donations led to the construction of a number of projects in Athens, as well as a number in Metsovo and the Greek community of Egypt. It was with his money that the Panathenaic Stadium received a new marble facing, the Hellenic Army Academy was erected, the statues of Rigas Feraios and Patriarch Gregorios V were made and set at the central building (Propylaea) of the University of Athens and the famous Averoff battleship was manufactured. He died in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1899. His statue is located at the entrance of the Panathenaic Stadium.

After Georgios Averoff died in 1899, a large part of his fortune was given over to fund the operation of schools, the construction of an aqueduct, springs and a bridge, the repair of public roads and churches, tree planting, the maintenance of a cemetery, the supply of free medicines to all Metsovo residents, poor girls were provided with dowries and the purchase of books was made for the creation of a public library.

The general supervision of the legacies and the schools was assigned to Georgios’ elder brother, Nikolaos Michael Averoff (Kolakis, son of Halis).

The Young Turk movement started in Thessaloniki under the initiative of the Committee known as “Union and Progress”. Their main slogan was “Freedom, Equality and Justice”. They focused mainly on the abolition of the totalitarian regime of Sultan Abdülhamid II, the restoration of the 1876 constitution and the modernisation of the state to match European standards. Moreover, the Young Turks wished to maintain the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, while advocating for equality in general and equality before the law for all citizens, regardless of their language and religious faith. The Young Turk movement was enthusiastically welcomed by the ethnic groups of the Ottoman empire. However, the Young Turks soon started implementing a Turkish nationalism programme with a view to creating a Turkish state with a uniform ethnic identity.

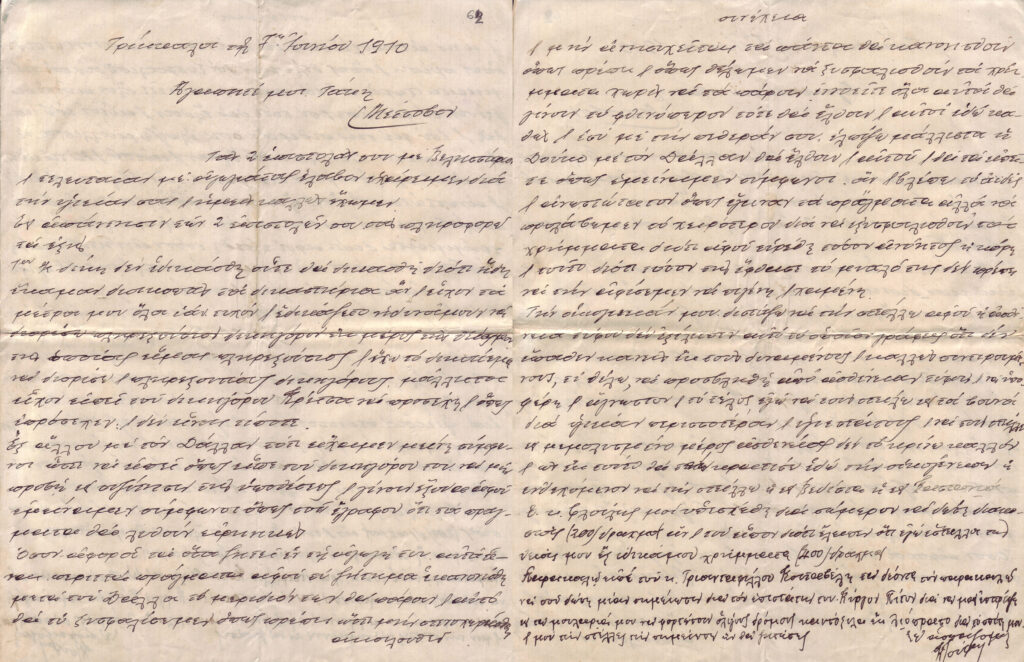

In 1910, an epidemic decimates the population of Metsovo.

In his letter dated early June 1910, K. Foufas who lived in Trikala wrote to D. Tsanakas in Metsovo: “I hesitate to send my family, since typhus has not been eradicated. You are saying that no fragile and well-fed citizen was affected, so what would I want [for them], to be affected by typhus and suffer without knowing if they are going to die? I may send them to the mountains to improve their health and become absolutely healthy, but I do not think it is a good idea to send them to an infected place full of sickness. I will keep the family here or maybe I will send them to Vedista or Kastania”.

The First Balkan War breaks out in October 5, 1912.

The First Balkan War was fought between the Balkan League – comprised of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro – and the Ottoman Empire. Within a few months the Ottoman Empire collapsed losing almost all of its European territories. However, Bulgaria’s wish for more land and especially its frustration at almost losing Macedonia, led to the Second Balkan War. On this occasion, Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, the Ottoman Empire and Romania joined forces against Bulgaria. The new war lasted just one month. It ended with the intervention of the European forces and led to the signing of the Treaty of Bucharest (July 1913). The Balkan Wars redrafted the map of the Balkan Peninsula. It was then that the independent Albanian state was founded. Serbia annexed Kosovo, Novi Pazar and part of Macedonia. Part of Macedonia was also annexed by Bulgaria (Bugaria calls it “Pirin Macedonia”), while Romania acquired south Dovroutsa. Greece received Epirus, a large part of Macedonia, the east Aegean islands and Crete.

In October 31, 1912, the Greek army frees Metsovo, leading to the end of Ottoman rule in the area.

During the last ten days of October 1912, groups of Cretan volunteers, along with a detachment consisting of 340 soldiers of the regular army, moved through the area of Thessaly to the Greek-Turkish borders that, at the time, crossed the eastern hills of Metsovo.

On October 31, 1912, at 6am, the Greek troops, helped by guerilla groups from Epirus and volunteers from Metsovo, attacked the Turkish guards which was made up of 205 soldiers and 2 cannon. Fighting lasted until 4pm, when the Ottoman soldiers, besieged in the fortress of Metsovo, raised the white flag of surrender.

GREEK STATE

1913-1939

The Balkan Wars changed the map of Europe. The Ottoman Empire lost almost all of its European territories while Greece doubled in size. From 1913 onwards, Metsovo belonged to the prefecture of Ioannina in the Greek state. The transition from the multi-national Ottoman empire to the Greek nation-state led to a series of political and economic transformations that inevitably affected the structure of the local society and the residents’ everyday life. From this point on, Metsovo would follow Greece’s fate and the people of Metsovo became part of the country’s political and social elite. The Asia Minor Catastrophe and the population exchange (1922-1923) marked the history of Greece but barely affected Metsovo, since it did not take in any refugees or lose any of its people. The interwar period was nevertheless a very troubled period, as Greece suffered political unrest, Europe saw the emergence of several fascist regimes and a world experienced an economic crisis. This period ended with the August 4 Dictatorship, imposed by I. Metaxas, which lasted until Greece entered World War II and Metaxas’ unexpected death.

1915-7: National Schism between Venizelos and Constantine regarding Greece joining World War I.

On May 27, 1917, Italian troops from the European alliance occupied Metsovo, firstly as a means of forcing Constantine and Greece into WWI and secondly because Italy planned to expand into Epirus. A plan for the foundation of a Vlach “Republic of Pindos” was unsuccessfully instigated. The Italians retreated on September 2, 1917.

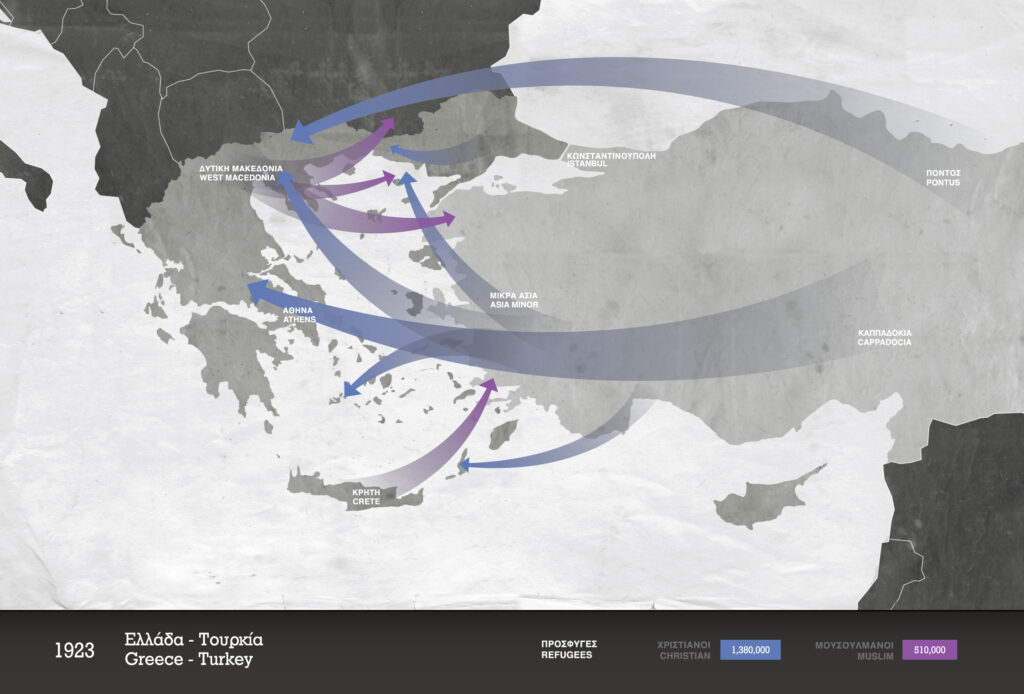

On July 24, 1923 the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, calling for a population exchange between Greece and Turkey. The exchange did not apply to the Muslim Cham Albanians of Epirus.

The Treaty of Lausanne brought the Asia Minor Catastrophe to a painful end whilst at the same time, ending the Greek war efforts that had begun with the Balkan Wars in 1912. East Thrace, Imbros, Tenedos and the Smyrna zone were conceded to Turkey while a compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey was decided upon. The exchange did not include the Muslims of West Thrace, the Greek Orthodox residents of Istanbul, Imbros and Tenedos, the Muslims of “Albanian nationality” living in Epirus (Chameria), or the Greek Orthodox Arabs residing in Cilicia.

In 1924, the Exarchate of Metsovo was abolished, by decision of the Synod, by the Patriarchate and was replaced by the Holy Metropolis of Metsovo, which was abolished in 1929. Metsovo was then subject to the Holy Metropolis of Grevena until 1932, when it was annexed to the Holy Metropolis of Ioannina.

The General Assembly of the residents of the community reacted to the decision to abolish the Holy Metropolis of Metsovo by sending two acts of protest in December 1929: one to the Ecumenical Patriarch and one to the Church of Greece. In their opinion the decision was unfair and they asked for the restoration of the Exarchate of Metsovo.

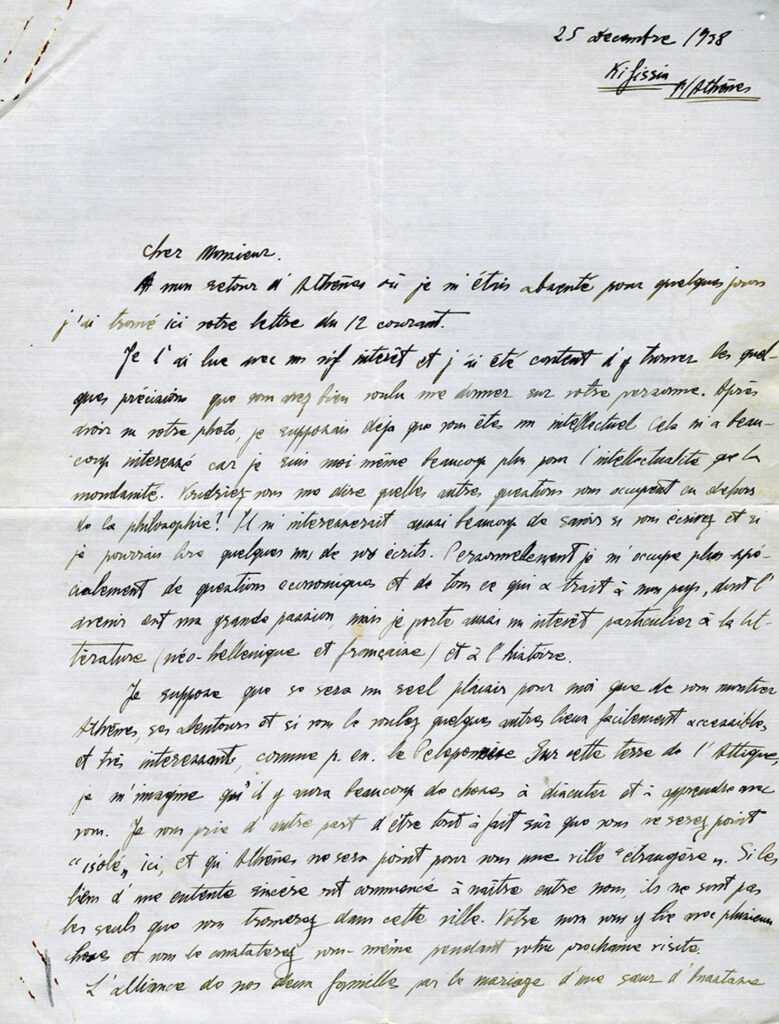

In 1937, the Cultural Association of Metsovo was founded; its president was Gregoris Tsanakas, the vice-president was Evangelos Averoff. The Association asked the diaspora of Metsovo to support Metsovo financially. This led to the exchange of letters between Evangelos Averoff and Baron Michael Tossizza, who was established in Lausanne and exiled from Greece. Their communication went on for many years.

In the first salvaged letter to Baron Michael Tossizza, dated December 1938, Evangelos Averoff writes: “…I imagine we will have a lot to discuss and learn from each other. (…) Your name is attached to many things here and you will see this on your visit soon.”

In another letter (1938), Averoff sent Tossizza pictures he had taken in Metsovo, to show him the village.

“Part of the village: the Church’s square, surrounded by the schools. The large building on the right is the primary school that was built in 1888 by Georgios Averoff. In the middle (the house with the two doors, one above the other) there is the School of Housekeeping and Weaving (G. Toulis Foundation) that I founded last summer. The second house behind the school is that of Nikolakis Averoff. A bit further to the right is your ancestors’ house, it cannot be seen though.”

On August 25, 1938, the School of Textile and Carpet Weaving was inaugurated at the Toulis Orphanage. A. Hatzimihali also participated in the initiative to found the school.

The construction of the Toulis Orphanage was funded by Georgios Toulis, a benefactor from Metsovo. In his will in 1878, Toulis, wrote: «the Orphanage will receive orphans who will be dressed in Frankish or European clothes made with double weaving (…) it is not to be a large building, but rather small and elegant, floors are to be laid and there are to be no basements, which are useless. Keep the rooms small and without fireplaces, add central heating to heat all rooms, as done in Wallachia.

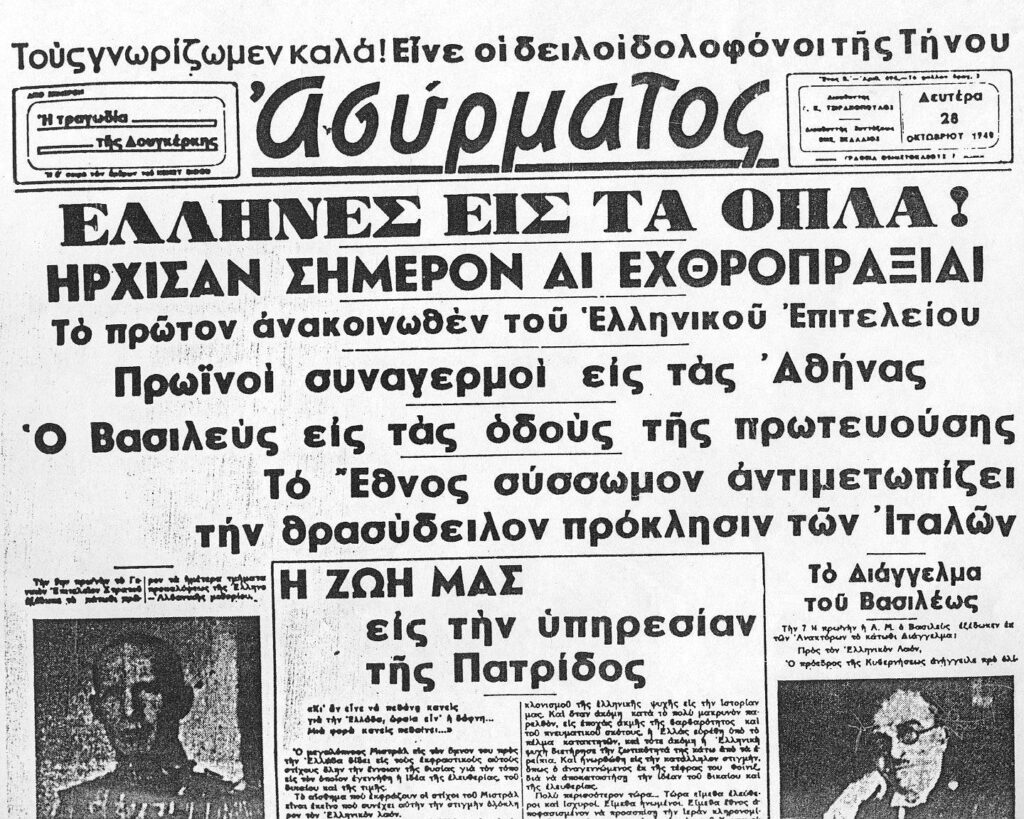

WORLD WAR II AND CIVIL WAR

1940-1949

The participation of Greece in WWII, after the negative response of I. Metaxas to the Italian ultimatum letter, introduced the entire Greek population and especially border areas, to a bloody confrontation with huge human and material losses. This small country fought first against Italy and then suffered the German invasion and the violent effects of that Occupation. Persecutions, executions and hunger marked the memories of people across the country. Populations were decimated, the economy destroyed along and the countryside depopulated. The retreat of the occupation troops from Greece in October 1944 did not bring an end to the war, as it did in the rest of Europe, as a new cycle of fighting – civil clashes – started between the Greek government army and the Democratic Army of Greece. The civil war ended with the defeat of the Democratic Army in August 1949 and left post-war Greece with a deep political and ideological schism.

In 1941-1942, Italy planned the foundation of an Autonomous Koutsovlach “Principality of Epirus” consisting of Pindos, west Macedonia and Thessaly. Italian propaganda declared the Aromuns (Vlachs) to be the descendants of the 5th Roman Legion – in other words descendants of the ancient Romans – and attempted, unsuccessfully, to entice the local populations in this way.

In 1947 the Baron Michael Tossizza Foundation was founded.

Thanks to Evangelos Averoff’s guidance, the Foundation played a key role in Metsovo’s economic growth and revival.

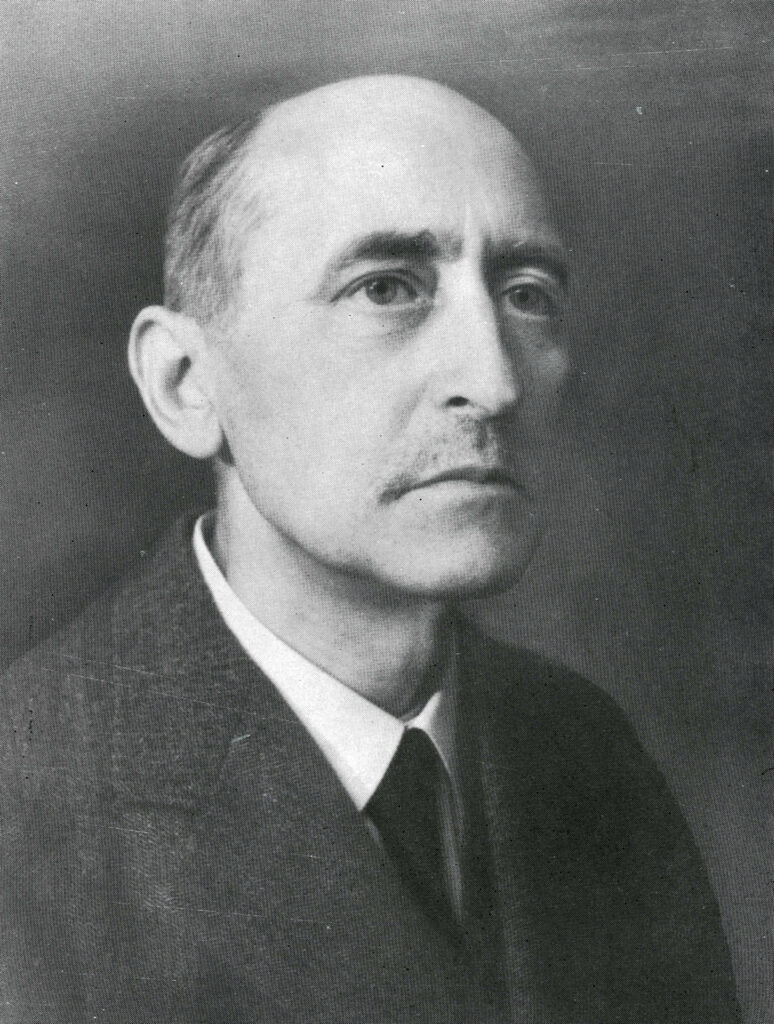

Baron Michael Tossizza (1885-1950) was the grandson of Konstantinos Tossizza, one of the youngest brothers of Greece’s national benefactor, Michael Tossizza (1787-1950), who had moved to Livorno, Italy, at the start of the 19th century. In 1831 the local duke awarded him the hereditary title of baron in recognition of the commercial activity of the Tossizza family.

Baron Michael Tossizza lived in Switzerland and France. Although he was not close to Greek life, he was persuaded, after the exchange of letters and communications with Evangelos Averoff, to found a charitable foundation to help the home of his ancestors. The foundation was established on June 1947 under the name of “Baron Michael Tossizza Foundation” and its main aim was the development of the wider area of Metsovo, from where its founder originated.

The foundation’s money was used to restore his family’s house in Metsovo (that still operates as a folk art museum) and the primary school building that had burnt down in 1947. It was also used for the creation of a hospital, a sawmill, a cheese-making plant, a gym, a ski centre, and various other social and development works. Over 107 schools were completed across the wider area of Epirus with funds provided by the foundations. Student accommodation was also built in Kato Kifisia to host students from Epirus.

Evangelos Averoff soon became involved in politics and for almost half a century he played a major role in Greek political life.

In 1941 he became Prefect of Corfu and in 1942 he was arrested by the Italians for his revolutionary activities. In 1946 he was elected member of parliament of Ioannina for the first time and then held the position of Deputy Minister and Minister of Supply, Finance and Agriculture. He was Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1956 to 1963.

During the military takeover he fought against the junta and was arrested. In 1974 he was assigned to the Ministry of Defence.

In addition to his political activity, he also wrote novels, stories, dramas, essays and historical analyses.

To Metsovo residents, Evangelos Averoff is the last representative of a long tradition of local benefactors. He led the initiative to create the Baron Michael Tossizza Foundation (which he managed for 40 years) that contributed greatly to the modern development of the settlement. It was at this point he also adopted the Tossizza name, in accordance with Baron Michael Tossizzas’ wish that all of the Foundation’s president bear his family name.

He also created the Evangelos Averoff- Tossizza Foundation, to which he donated his extremely valuable and important personal collection of Greek painters of the 19th and early 20th century, building a gallery to host them. At the same time, he invested in local wine making by cultivating the abandoned Metsovo vineyard and by creating a modern winemaking plant.

POST – WAR PERIOD

1950-1974

The reconstruction of Greece after almost a decade of fighting was hard and painful. From now on, the international Cold War loomed over domestic political developments to a huge extent. During the initial post-war decades, there was huge immigration from a largely agricultural Greece to industrially developed countries, such as the USA, Canada, Germany and Australia. The rural population also started to migrate into cities that were now growing larger (especially the capital) massively changing domestic demographics. At the same time, new goods and technologies, such as the TV and domestic appliances, were arriving from the West and having an impact on everyday life. The years following 1960 saw an increase in mass tourism, the development of the construction industry (housing and infrastructure works) and the transformation of Greek society. The dictatorship of the Colonels (1967-1974) ended with the coup d’état against Makarios and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. The monarchy was abolished via referendum.

In 1955, King Paul visited Metsovo to inaugurate the Folk Art Museum that had been built by the Baron Michael Tossizza Foundation.

Paul I was born in 1901, son to Constantine I and Sofia. In 1938 he married Princess Frederica of Hanover and they had three children: Sofia, Constantine and Irene. In 1947, after his childless brother George II died, he came to the throne during a period of hardship for Greece. In the decades that followed, a balance between the Crown and the political parties became difficult to achieve. The constant involvement of Paul, as well as his wife, Frederica, in Greek politics caused frustration and conflict, with the likes of Marshal Al. Papagos and, later with K. Karamanlis. Paul died in 1964 and was succeeded by his son Constantine.

On December 8, 1974, the monarchy was dissolved via referendum.

The monarchy was established in Greece in the London Protocol (1830) that provided for the creation of an independent Greek state. The first king was Otto, second son of king Ludwig I of Bavaria (Wittelsbach dynasty). After Otto was removed in 1862, George, the second son of the future king of Denmark, Christian IX, was appointed King of Greece (a scion of the Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg dynasty). This dynasty ruled through many exploits, schisms and a number of intermittent breaks in democracy, until 1974.